A range of works from the Mughal era, including the prestigious album of two East India Company officers depicting richness of Delhi’s ceremonial life, will go under the hammer at Bonhams, Londo.

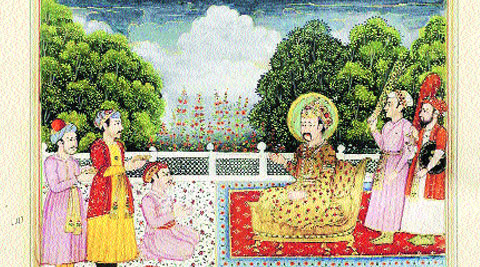

The enigma called Delhi drew several explorers back then. Travelling across waters to witness life in the Mughal Capital, they were intrigued by its holy men, Afghan horse dealers and ascetics. The Fraser brothers were no different. While 16-year-old William arrived in India in 1814 as a trainee political officer in the East India Company, his brother James took a commercial position in Calcutta. Together the duo was to explore and document the India that was untouched by the West. The pages from their album are now a memoir of the period. The 90 watercolours that comprise it provide a portrait of life in and around Delhi in the early 19th century. On April 8, Bonhams will auction three works from the prestigious album in the London sale of Indian and Islamic art. “The lots capture the richness of ceremonial life in Delhi and are representative of British fascination with types of transport and servants that appear in other more typical examples of Company School painting. It combines Mughal and European styles,” says Matthew Thomas, Specialist, Islamic and Indian Art, Bonhams, about the works dated between 1815-19.

Discovered among the papers of the Fraser family in 1979, each work is estimated between £20,000-30,000. “The circumstances of its commission and the lives of the Fraser brothers add an almost romantic element to the album, as does its emergence from the family’s papers in 1979 and its first appearance in the salerooms in 1980,” notes Thomas.

The first image is of an elephant and a driver, probably from the Mughal Emperor’s stable, with a hunting howdah (carriage positioned on the back of an elephant) equipped with a rifle, bows and a pistol. The second image is the bullock-drawn carriage of Prince Mirza Babur and the third is that of a cotton-carder at work. It has been attributed to the artist Ghulam Ali Khan and depicts the tedious process of “bowing” or running the taut string of the bow across the pile of fibres to fluff up the cotton.

In addition to the prestigious works from the album, among the total of 306 lots are a group of 61 Kalighat paintings from the 19th century (£ 50,000-70,000) and late 17th century Mewar painting of Mughal emperors Akbar, Jehangir, Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb. Great Indian Fruit Bat, a painting from the Impey Album (commissioned by wife of Sir Elijah Impey, East India Company’s Chief Justice of Bengal from 1774 to 1782) by artist Bhawani Das is estimated at £80,000-1,20,000. Also, among the highlights are The Book of Kings and The Book of Akbar. Lavishly illustrated with 110 miniatures, the former is the great Persian epic poem by Firdausi, copied by the scribe Nizam-ad-Din. The latter, estimated between £30,000 and 50,000, is illustrated with 65 miniatures. Coming from the collection of Nathaniel Middleton (East India Company Resident in Lucknow, 1776-1782), the 18th century Persian manuscript on cream-coloured paper features 508 leaves.

Even as Mathew invites bids for the coming auction, he notes that the interest in antique works is on a rise. “In India there has been an increasing interest in these works, where before interest was largely confined to modern Indian paintings,” he notes.